The Dispossession of SmallholdersIn the small countries of Central America, a couple of U.S.-based banana companies have wielded enormous influence. The United Fruit Company (now known as Chiquita) acquired so much power in Guatemala and Honduras that it came to function as a state within a state, giving rise to the notion of “banana republics.” Here’s how it all started. |

The Dispossession of SmallholdersIn the small countries of Central America, a couple of U.S.-based banana companies have wielded enormous influence. The United Fruit Company (now known as Chiquita) acquired so much power in Guatemala and Honduras that it came to function as a state within a state, giving rise to the notion of “banana republics.” Here’s how it all started. |

|

In the early 1880s, a young fellow named Andrew Preston would go down to the docks in Boston to bargain for whatever fruits and vegetables had come in on the latest ship. The junior assistant to a produce seller, Preston saw potential in bananas. In 1885, he persuaded nine men to give him two thousand dollars each, with the hope of making a profit within five years. With this capital, Preston teamed up with Lorenzo Baker to form Boston Fruit, the earliest incarnation of what would become, after a series of name changes, today’s Chiquita. Together, the two began a gradual process of vertical integration. Baker purchased the fruit in the Caribbean and shipped it north, while Preston created retail markets for bananas in the United States. Boston Fruit invented large-scale refrigerated shipping by setting up a chain of cold-storage warehouses all along the shipping routes from ports to railroad depots. They called this subsidiary the Fruit Dispatch Company. By slowing down the ripening process, the company could expand its consumer base farther from where the fruit was grown.

Back in Central America, a young entrepreneur from Brooklyn secured a contract to build a national railroad in Costa Rica. Strapped for cash, the young republic granted Minor C. Keith a ninety-nine-year concession that gave him 800,000 acres of land along the tracks and a monopoly on the railroad route from San José to the Caribbean port of Limón. Between 1871 and 1880, over four thousand workers died building the railroad. Malaria, yellow fever, dysentery, and dehydration wiped out successive workforces. As historian Aviva Chomsky writes, “Railroad baron Minor Keith experimented with Central American, European, and Asian laborers in his construction projects in Limón, but it was Jamaicans who proved to be the cheapest and most accessible laborers.”i Keith soon discovered that he could plant bananas on that land and use his railroad to get them to port. The bananas were much more profitable than the railroad. He began running a steamboat line from Limón to New Orleans. Within a few years, he had set up banana plantations in Panama and in Magdalena, Colombia.

And then Keith’s creditors came knocking. He was unable to repay loans that he had taken out in Britain. Baker and Preston saw an opportunity. Their Boston Fruit Company was dominating the banana business in the Caribbean and the East Coast markets, while Keith’s business reigned over Central America and the southern and southwestern markets of the United States. In 1899, they combined forces to create a new company—United Fruit—with Preston as president and Keith as vice president. |

|

In the early 1880s, a young fellow named Andrew Preston would go down to the docks in Boston to bargain for whatever fruits and vegetables had come in on the latest ship. The junior assistant to a produce seller, Preston saw potential in bananas. In 1885, he persuaded nine men to give him two thousand dollars each, with the hope of making a profit within five years. With this capital, Preston teamed up with Lorenzo Baker to form Boston Fruit, the earliest incarnation of what would become, after a series of name changes, today’s Chiquita. Together, the two began a gradual process of vertical integration. Baker purchased the fruit in the Caribbean and shipped it north, while Preston created retail markets for bananas in the United States. Boston Fruit invented large-scale refrigerated shipping by setting up a chain of cold-storage warehouses all along the shipping routes from ports to railroad depots. They called this subsidiary the Fruit Dispatch Company. By slowing down the ripening process, the company could expand its consumer base farther from where the fruit was grown.

Back in Central America, a young entrepreneur from Brooklyn secured a contract to build a national railroad in Costa Rica. Strapped for cash, the young republic granted Minor C. Keith a ninety-nine-year concession that gave him 800,000 acres of land along the tracks and a monopoly on the railroad route from San José to the Caribbean port of Limón. Between 1871 and 1880, over four thousand workers died building the railroad. Malaria, yellow fever, dysentery, and dehydration wiped out successive workforces. As historian Aviva Chomsky writes, “Railroad baron Minor Keith experimented with Central American, European, and Asian laborers in his construction projects in Limón, but it was Jamaicans who proved to be the cheapest and most accessible laborers.”i Keith soon discovered that he could plant bananas on that land and use his railroad to get them to port. The bananas were much more profitable than the railroad. He began running a steamboat line from Limón to New Orleans. Within a few years, he had set up banana plantations in Panama and in Magdalena, Colombia.

And then Keith’s creditors came knocking. He was unable to repay loans that he had taken out in Britain. Baker and Preston saw an opportunity. Their Boston Fruit Company was dominating the banana business in the Caribbean and the East Coast markets, while Keith’s business reigned over Central America and the southern and southwestern markets of the United States. In 1899, they combined forces to create a new company—United Fruit—with Preston as president and Keith as vice president. |

Overseer's house - $4,000, circa 1922.

United Fruit Company Photograph Collection, Baker Library, Harvard Business School (olvwork729861)

Overseer's house - $4,000, circa 1922.

United Fruit Company Photograph Collection, Baker Library, Harvard Business School (olvwork729861)

| Costa Rica’s exchange of its land for the construction of a railroad would be repeated in Honduras and Guatemala, but even more scandalously. Governments that were broke and desperate to link their countries to the global north borrowed money and gave away their most fertile land in exchange for promises of railroads. In 1902, the Honduran government gave William F. Streich of Philadelphia a large land concession. In return, Streich was charged with building a five-mile stretch of railroad from Cuyamel to Vera Cruz so that Honduran banana producers would not be dependent upon river barges to get their goods to the port of Omoa. The Central American republics wanted infrastructure—ports and railroads—and the North American entrepreneurs wanted vast stretches of land. But the companies took the land and tax breaks without building railroads that could serve local populations or other industries. |

| Costa Rica’s exchange of its land for the construction of a railroad would be repeated in Honduras and Guatemala, but even more scandalously. Governments that were broke and desperate to link their countries to the global north borrowed money and gave away their most fertile land in exchange for promises of railroads. In 1902, the Honduran government gave William F. Streich of Philadelphia a large land concession. In return, Streich was charged with building a five-mile stretch of railroad from Cuyamel to Vera Cruz so that Honduran banana producers would not be dependent upon river barges to get their goods to the port of Omoa. The Central American republics wanted infrastructure—ports and railroads—and the North American entrepreneurs wanted vast stretches of land. But the companies took the land and tax breaks without building railroads that could serve local populations or other industries. |

|

Short on funds, Streich was looking to sell his land. Onto the scene walked an immigrant from Russia who had arrived in the United States in 1892, changing his name from Schmuel Zmurri to Samuel Zemurray. He had gotten his start selling bananas from a pushcart in Mobile, Alabama. From there, he began shipping them upcountry along the railroad, which United Fruit came to resent. The company made Zemurray an offer: in exchange for relinquishing his contract to sell ripe fruit, the company would give him the capital that he needed to buy Streich’s property and rights. He took it, and then purchased a battered old steamer that he conducted to and from the port of Omoa. His business grew rapidly. In 1903, he sold 336,000 bunches of bananas. Just seven years later, he sold 1.75 million bunches and established the Cuyamel Fruit Company.

“The United Fruit Company consolidated its power through various means: it installed authoritarian civilian and military governments that gave concessions to land, railroads, and ports; it divided its labor force along ethnic and racial lines; it built hospitals, schools, workers’ barracks, and houses for its management; and it used massive amounts of pesticides and herbicides in a capital intensive effort to cultivate varieties of the fruit that North American consumers came to expect but which were susceptible to Panama disease and Black Sigatoka.”— AVIVA CHOMSKY, WEST INDIAN WORKERS, 1

|

|

Short on funds, Streich was looking to sell his land. Onto the scene walked an immigrant from Russia who had arrived in the United States in 1892, changing his name from Schmuel Zmurri to Samuel Zemurray. He had gotten his start selling bananas from a pushcart in Mobile, Alabama. From there, he began shipping them upcountry along the railroad, which United Fruit came to resent. The company made Zemurray an offer: in exchange for relinquishing his contract to sell ripe fruit, the company would give him the capital that he needed to buy Streich’s property and rights. He took it, and then purchased a battered old steamer that he conducted to and from the port of Omoa. His business grew rapidly. In 1903, he sold 336,000 bunches of bananas. Just seven years later, he sold 1.75 million bunches and established the Cuyamel Fruit Company.

“The United Fruit Company consolidated its power through various means: it installed authoritarian civilian and military governments that gave concessions to land, railroads, and ports; it divided its labor force along ethnic and racial lines; it built hospitals, schools, workers’ barracks, and houses for its management; and it used massive amounts of pesticides and herbicides in a capital intensive effort to cultivate varieties of the fruit that North American consumers came to expect but which were susceptible to Panama disease and Black Sigatoka.”— AVIVA CHOMSKY, WEST INDIAN WORKERS, 1

|

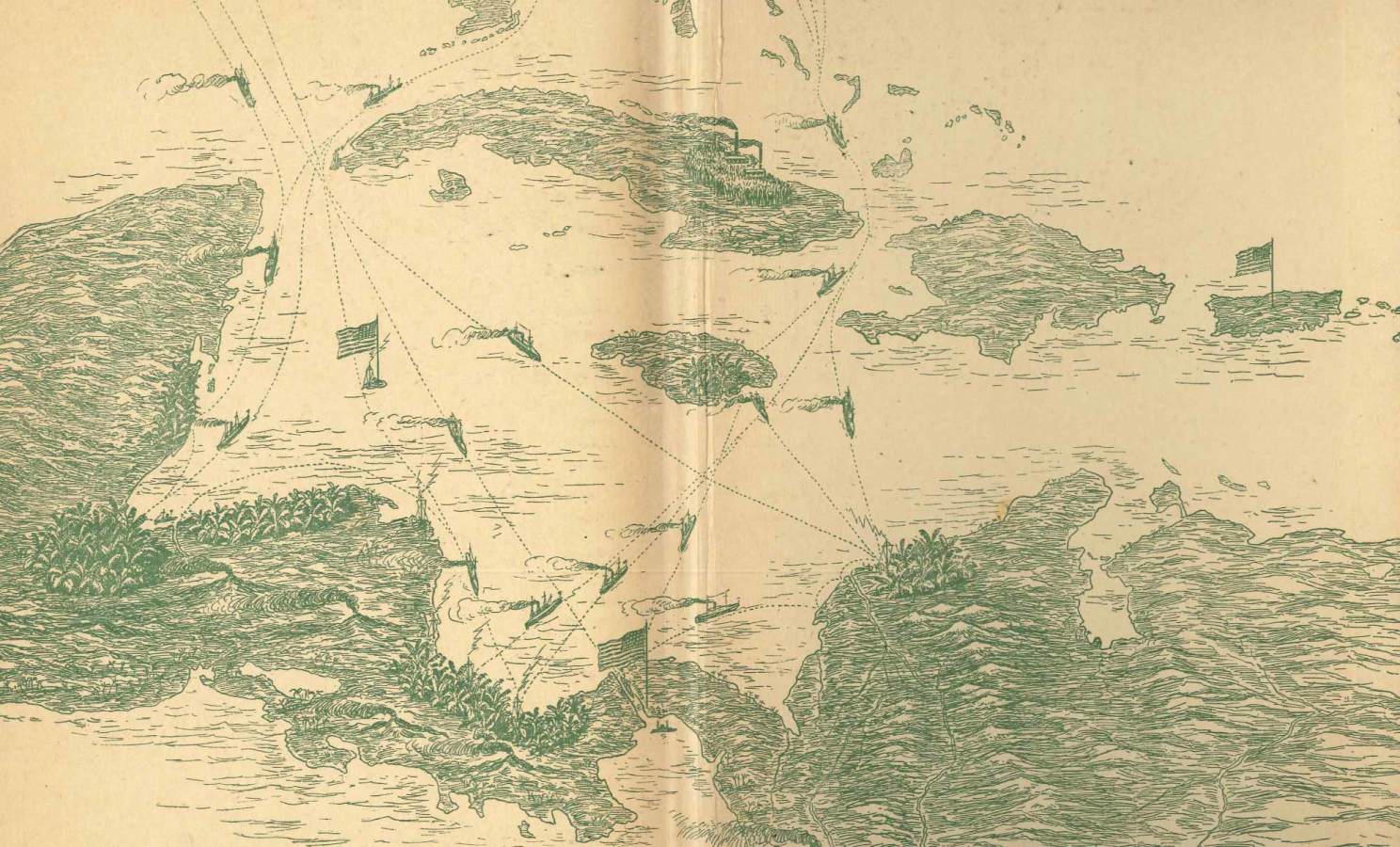

| In late December 1910, Zemurray gave his friend Manuel Bonilla, a former president of Honduras, money to purchase a yacht called The Hornet. Just outside New Orleans, according to Hermann Deutsch, a newspaper reporter who was based there, The Hornet rendezvoused with Sam “The Banana Man” Zemurray’s forty-foot cruiser to pick up “General Lee Christmas and his lieutenant, Machine Gun Molony, a case of rifles, 3,000 rounds of ammunition and a machine gun.”ii The rebel ship then sailed to Roatán, an island off the coast of Honduras that had been used in a previous era by British pirates to harass outgoing Spanish vessels, and Trujillo, a colonial-era port city. The rebels captured Trujillo on January 10, 1911. Soon the sitting president of Honduras was sending urgent cables to President William Howard Taft, agreeing to the loan from J.P. Morgan and Company and pleading for U.S. intervention to stop the banana mercenaries. But the U.S. Senate rejected the agreement (known as the Paredes-Knox Convention), and the New York bank declared that it was no longer prepared to purchase the bonds. Soon after, the U.S. consul took the various factions aboard the U.S.S Tacoma. A new president, one backed by Zemurray’s rebels, emerged from the meeting. Less than a year later, Manuel Bonilla returned to the presidency.iii |

| In late December 1910, Zemurray gave his friend Manuel Bonilla, a former president of Honduras, money to purchase a yacht called The Hornet. Just outside New Orleans, according to Hermann Deutsch, a newspaper reporter who was based there, The Hornet rendezvoused with Sam “The Banana Man” Zemurray’s forty-foot cruiser to pick up “General Lee Christmas and his lieutenant, Machine Gun Molony, a case of rifles, 3,000 rounds of ammunition and a machine gun.”ii The rebel ship then sailed to Roatán, an island off the coast of Honduras that had been used in a previous era by British pirates to harass outgoing Spanish vessels, and Trujillo, a colonial-era port city. The rebels captured Trujillo on January 10, 1911. Soon the sitting president of Honduras was sending urgent cables to President William Howard Taft, agreeing to the loan from J.P. Morgan and Company and pleading for U.S. intervention to stop the banana mercenaries. But the U.S. Senate rejected the agreement (known as the Paredes-Knox Convention), and the New York bank declared that it was no longer prepared to purchase the bonds. Soon after, the U.S. consul took the various factions aboard the U.S.S Tacoma. A new president, one backed by Zemurray’s rebels, emerged from the meeting. Less than a year later, Manuel Bonilla returned to the presidency.iii |

![]()

|

LINKS – Chiquita Banana Commercial. United Fruit Company, 1950s.

– Chomsky, Aviva. West Indian Workers and the United Fruit Company in Costa Rica, 1870–1940. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996.

i. Chomsky, West Indian Workers, 1. |

![]()

|

LINKS – Chiquita Banana Commercial. United Fruit Company, 1950s.

– Chomsky, Aviva. West Indian Workers and the United Fruit Company in Costa Rica, 1870–1940. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996.

i. Chomsky, West Indian Workers, 1. |